Estimated reading time:20 minutes, 42 seconds

The pandemic has lifted the lid across business sectors on just how bad many businesses are ran by their owners. However, in the interest of sport, we take a look at the state of the Premier League and what came out during COVID was shocking.

Some clubs in the Premier League and the Championship stated very quickly after the first lock down that they couldn’t last more than 3 or 4 months without government help/ tax payers money which is a disgrace. Especially, when many of those tax payers wouldn’t be able to afford a ticket at a Premier League or Championship match. Plus, its shows you the true state of football for many clubs throughout the football pyramid.

With the amount of money being invested into football and the amount of money spent on football from the commercial sector. Clubs should not be on the verge off collapse after a few months, and should have a surplus of money generated from revenue due to many years at the top level of football. The fact they don’t have a surplus for rainy days is a failure by the clubs, their leagues, the associations, UEFA and FIFA who govern them, this should not be happening.

It is Futsal Focus hope that those within Futsal will learn from the mistakes and mismanagement within the football industry. We are in the perfect position now, whilst futsal is still amateur in most nations, to learn from and use the football industry as a benchmark for what not to do going forward, if we want to keep our sport as competitively fair as possible.

Here is a great article by Athletic Football News, please read this insightful article by this quality media sports platform:

The ‘challenging’ state of Premier League finances and how the Big Six operate in a world of their own

It was a year that saw Liverpool celebrate their first English title in 30 years only for their auditor to raise doubts about the club’s ability to meet its financial obligations.

It was a season when income across the Premier League fell by about £600 million but England’s top-flight clubs still combined for a net spend of more than £900 million in the summer transfer window.

It was a campaign when clubs furloughed or laid off staff, extended overdrafts and saw profits vanish but still increase their wage bills by nearly 10 per cent.

“Naturally, each year my foreword is filled with reflections,” wrote Everton chairman Bill Kenwright, the theatre impresario with the Premier League’s most florid pen.

“Reflections of the highs and lows of our teams over the last 12 months, reflections and memories of those we’ve sadly lost and reflections that, I hope, give us reason to be optimistic for the year ahead. And this year, all these emotions have been there again — but more intense and more profound than at any other time I can remember.”

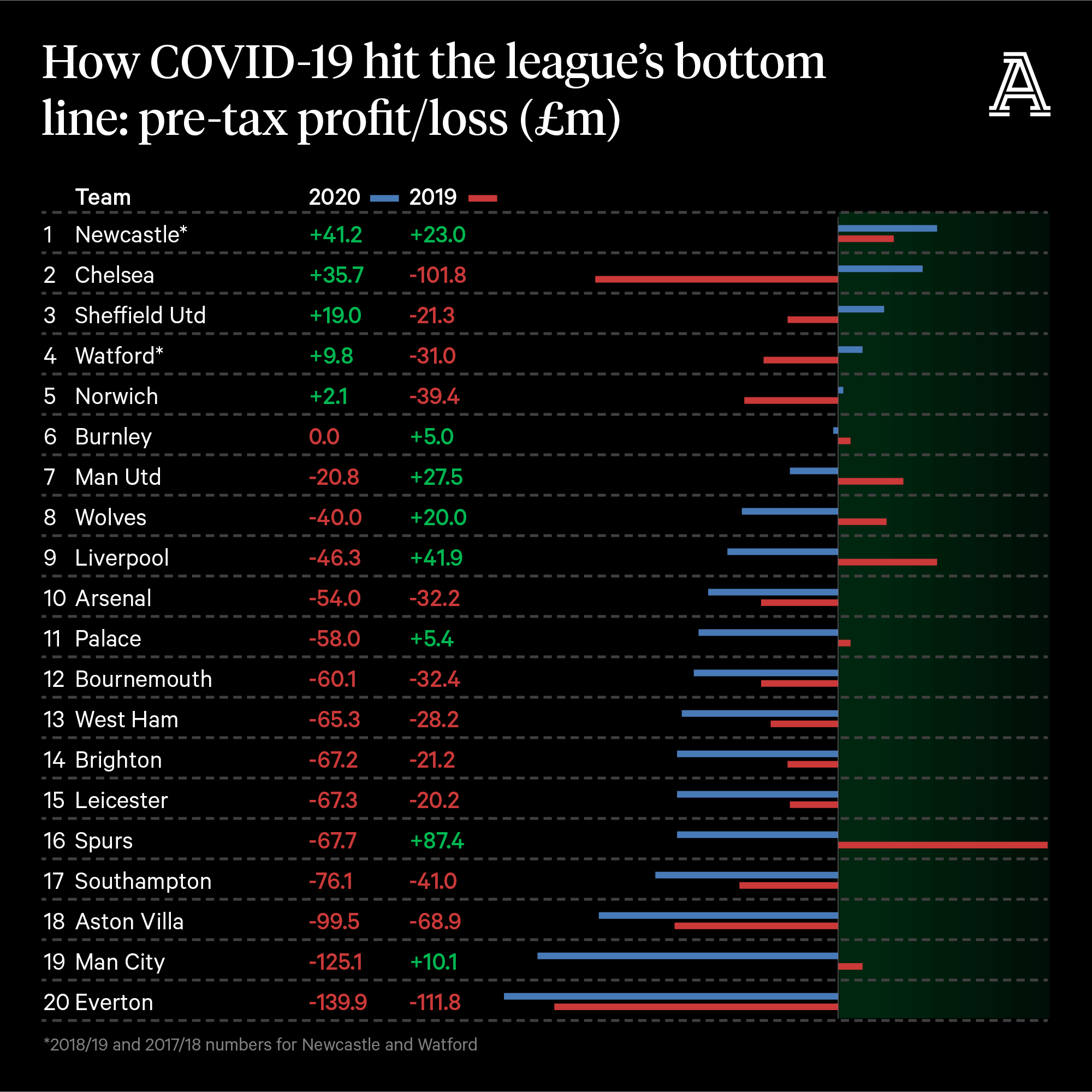

Kenwright was writing in his club’s financial report for 2019-20: 46 pages of otherwise sober text that explained how Everton managed to lose the most money in the Premier League for the second straight year. “In such a challenging year, particularly in financial terms, we should be hugely thankful to have such a committed owner in Farhad Moshiri,” he added.

Seventeen of the 20 clubs in the Premier League in 2019-20 have posted their financial accounts, with an 18th, Crystal Palace, revealing headline figures via a press release in a dark corner of their website. Only serial late-filers Newcastle United and Watford are still to tell us just how “challenging”, “turbulent” and “unprecedented” last season was but we have got the picture and it is… fuzzy.

A year ago, The Athletic published its first annual assessment of Premier League club accounts and revealed just how many of them were already stretched at the start of the worst crisis the game has faced since World War II. So should we be surprised that broadcaster rebates and locked turnstiles plunged most of them into the red?

If anything, the surprise is that the losses are not worse, although it is probably best if we view last season as the first leg in a bruising two-leg cup tie. Seen through that lens, most have grimly held on to give themselves a shout of progressing at the halfway point.

There are lessons to draw from these snapshots, though, and that is what we will explore here. But before we do that, we should explain our approach.

We are only looking at clubs that were in the Premier League last season, which means Bournemouth, Norwich City and Watford are in, and Fulham, Leeds and West Bromwich Albion are out. The financial divide between the Championship and the top flight is just too wide to make meaningful comparisons.

But, like last year, we are focusing on total earnings and each club’s main expense: the wage bill for the entire club, not just the players. And with some clubs using historic tax credits to mitigate losses, we are again using the pre-tax profit/loss figure.

Right, let’s dive in…

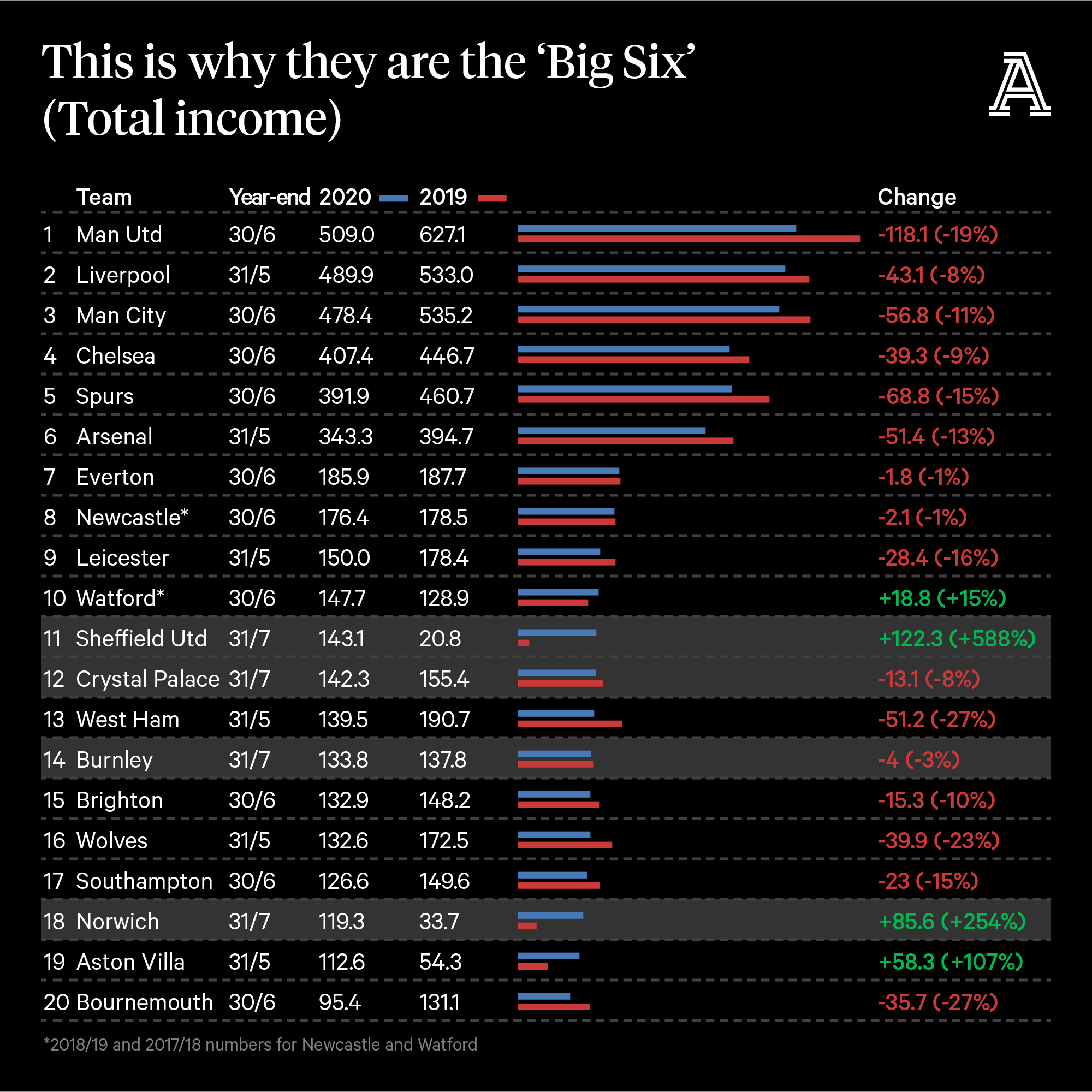

Premier League clubs combined to earn about £5.1 billion in 2018-19 but, with only Newcastle and Watford to come, the 2019-20 total is at just over £4.2 billion. The two laggards should bump that up to £4.5 billion, a year-on-year decline of around £600 million, the combined income of the five lowest earners in the league.

Ouch, right?

Yes, ouch, since half of that money is never coming back. The two main components here are the missing match-day income from the games played behind closed doors when the season resumed in June — each club had at least four home games left — and a broadcasters’ rebate of £330 million. That will be clawed back in reduced payments over two years — on a pro-rata basis, with champions Liverpool paying the most and last-placed Norwich the least — but the clubs have accounted for the largest slice in their 2019-20 numbers.

The other half, 92 games’ worth of broadcast cash from June and July, has not gone, it is just delayed. Clubs can only claim this income as it is earned, which means almost a quarter of the season came too late for financial years that traditionally finish on May 31 or June 30.

Arsenal, for example, which has a year-end of May 31, can add the income from their last 10 league games to this season’s accounts, as well as money earned from their wins in the FA Cup’s quarter-finals, semi-finals and final.

Manchester City, on the other hand, have a year-end of June 30, so their 2020-21 numbers will be boosted by the seven league games they played in July, the FA Cup semi-final they lost to Arsenal, and August’s Champions League last-16 second-leg win over Real Madrid and quarter-final defeat to Lyon.

Sixteen of last season’s Premier League sides, however, decided to stick to their traditional accounting periods, even if deferring almost a quarter of their broadcast income tipped several of them into net losses for the year. Wolverhampton Wanderers, to pick just one, signed for a pre-tax loss of almost £40 million but would have made a small profit if they had been able to include the TV loot earned in June, July and August. Manchester United are another who would have avoided the embarrassment of ending a season in the red.

The big split among the Big Six

They are the clubs that already hold most of the cards but still moan about the hands they have been dealt: the Big Six who (briefly) joined the Dirty Dozen in a so-called Super League and became the Silly Six.

Ever since 2007, when Tottenham Hotspur finally got ahead and stayed ahead of Newcastle United in the annual turnover stakes, the same clubs have topped the Premier League’s tables for money in and money out.

Arsenal, Liverpool and Manchester United, English football’s most successful clubs in terms of trophies, have always been big, of course, while Chelsea and Manchester City emerged from the chasing pack like express trains.

Tottenham, on the other hand, were good enough at the moment the Premier League’s global popularity and UEFA’s Champions League rewards exploded, compounding influences that helped the Big Six disappear into the distance.

Good luck or good management? Having climbed to fifth in the Premier League’s income charts and ninth in Deloitte’s Money League, ahead of fellow conspirators Juventus, Arsenal, Atletico Madrid and the two Milan clubs, Tottenham chairman Daniel Levy could be forgiven for saying, “Who cares? Can you leave a team with a stadium like ours out of a Super League?”

And if Spurs were fortunate to be one of the league’s better teams at just the right moment in the game’s history, you would also have to acknowledge they have been unlucky to open the best sports venue in Europe just before a pandemic shut them all.

Having accounted for at least 50 per cent of the league’s income every season since 2004, the six richest clubs claimed 58 per cent of the total last year. In truth, that share is likely to be higher once the deferred broadcast income is included, as none of them stretched their accounting periods.

All six experienced declines in their match-day revenue (both north London teams and Manchester United would normally make more than £100 million in match-day revenue) and all but Chelsea grew their commercial income. Not that Chelsea minded too much, as they have posted the biggest pre-tax profit so far, thanks to the big-ticket sales of Eden Hazard and Alvaro Morata.

A third season without Champions League football is the chief reason Arsenal drifted to the bottom of the Premier League’s elite subset and to 11th (from a high of fifth between 2008 and 2010) in Deloitte’s global rich list.

In fact, you could argue there are two halves developing within the Big Six, with a revenue gap of at least £70 million existing between the third-placed team and the fourth for the second year in a row. In 2019, that was Liverpool and Spurs, respectively, adversaries in that year’s Champions League final. Last season, it was Manchester City and Chelsea, as Liverpool’s Premier League title win helped them climb over City into second place, and Spurs fell to fifth after a season of Thursday night football.

If there is a lesson here it is that all UEFA-related prize money is good but Champions League prize money is better. Much better.

Manchester United provided the best illustration of this last season with a dramatic slide in total revenue of £118 million, or about what Norwich earned in their 13-month stay in the Premier League. More than half of that decline can be blamed on the difference between reaching the quarter-finals of Champions League in 2019, an accomplishment that earned United £83 million, and the booby prize of a run to the semi-finals of the Europa League last year, worth only £17 million.

United’s decline in revenue was the biggest in percentage terms among their peers and saw them slide to fourth in the Deloitte list, a ranking they topped between 1997 and 2004 and again between 2015 and 2017.

That second spell on top came under their current owners, the Glazers, which explains why their ambassador to earth, executive vice-chairman Ed Woodward, once remarked that United do not need to win to make money. That is still true but it is not an experiment Woodward’s successor should try for much longer.

His erstwhile boss Joel Glazer put it like this in October when he listed the main risks United face in his introduction to the club’s accounts. “The success of our business depends on the value and strength of our brand and reputation,” he explained. “Failure to respond effectively to negative publicity could also further erode our brand and reputation.

“The loss of our followers’ commitment could impair our ability to expand our follower base, sponsors and commercial partners or our ability to sell significant quantities of our products, which could result in decreased revenue across our revenue streams and have a material adverse effect on our business.”

Well, at least he recognises that weeks of dreadful press, even worse social media and a pitch invasion that gets one of the biggest games of the season postponed might be bad for the bottom line. Eight seasons without a genuine title challenge had not cut through in Florida.

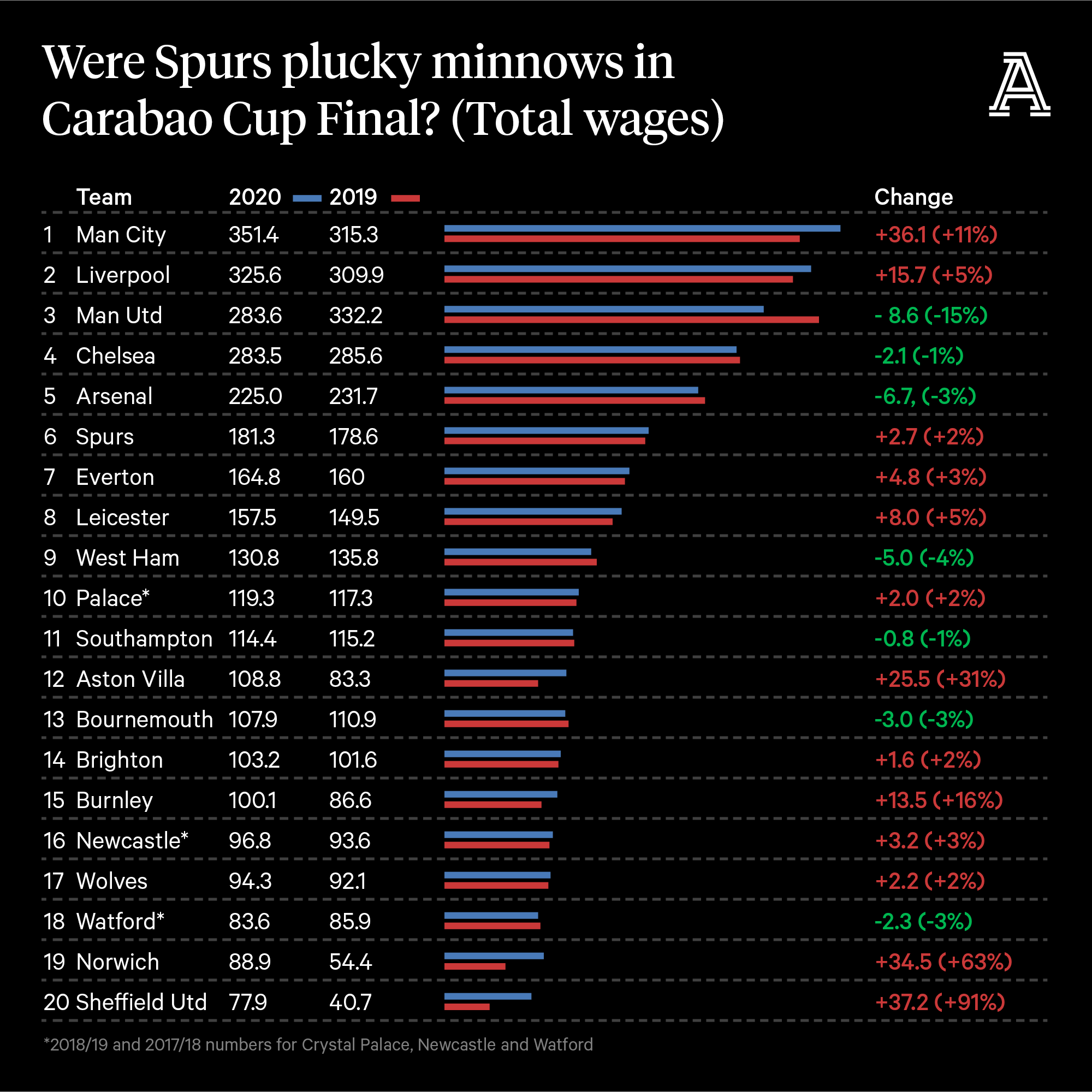

There should be so many alarm bells ringing at the various Glazer mansions right now, another one is unlikely to make any difference but perhaps the most significant numbers in all of the 2019-20 Premier League club accounts are these: £351.4 million, £325.6 million and £283.6 million, the wage bills of Manchester City, Liverpool and Manchester United. In that order.

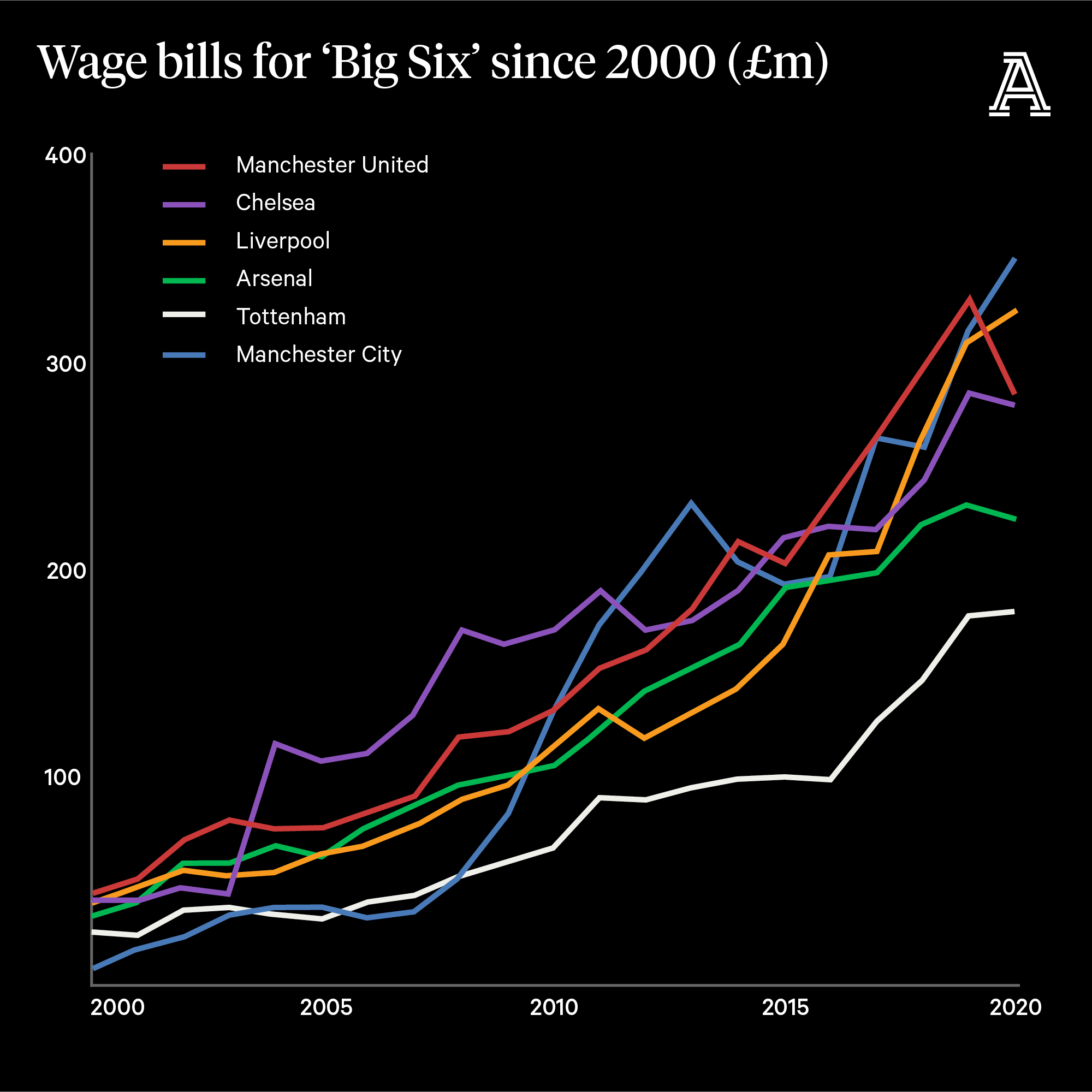

When the Premier League was launched in 1992, United and Liverpool topped the salary charts with payrolls of £8 million each. As Sky’s pay-TV subscription money started to transform the league, Liverpool’s wage bill of £30 million topped that of their great rivals in 1997-98, only for United to retake the top spot a season later. Roman Abramovich knocked United into second place again from 2004 to 2010, when Manchester City’s wage bill shot up like one of Abu Dhabi’s new skyscrapers, making it a three-way contest to be the Premier League’s biggest payers.

But United regained their perch in 2016 with a total spend on salaries of £215 million and stayed there until last season, when they sliced nearly £50 million (15 per cent) off their payroll and Liverpool dished out bonuses for winning the Champions League. That added five per cent to their wage bill, taking them to £326 million, putting Liverpool ahead of United for the first time in more than two decades.

However, dashing past both of them, with only Carabao Cup bonuses to meet, were Manchester City, with an 11 per cent increase to £351 million — a new Premier League record and almost £70 million clear of their crosstown rivals. And this is before they signed Nathan Ake, Ruben Dias or Ferran Torres in last summer’s window and long before they gave Kevin De Bruyne a new contract.

It should also be noted that much of City’s senior management is paid by City Football Group (CFG), the global empire now comprised of 10 clubs in five continents, although CFG does charge City for these services via a different column in the club’s accounts.

The upshot of all this spending — coupled with a significant chunk of deferred broadcast revenue, the lost match-day income, the rebate and their reduced £9 million fine for breaching UEFA’s financial fair play rules — was a £125 million net loss. This was City’s first loss for six years and the fourth-worst in Premier League history. Another impending Premier League title, a fourth straight Carabao Cup win and the club’s first Champions League final is, at least, a decent return on their investment.

Or, as City chief executive Ferran Soriano drily put it in his introduction to the club’s financial report: “Clearly, the 2019-20 accounts in isolation are not the best representation of the reality of the season. A better financial picture of the COVID years will be provided at the end of 2020-21 when the two seasons are combined and normalised.”

Well, quite.

Mind the gap — life outside the Big Six

No matter how you slice it, the Big Six really are operating in a world of their own. The revenue gap between Arsenal in sixth and Everton in seventh was £157 million last year, or more than Leicester City earned in ninth place.

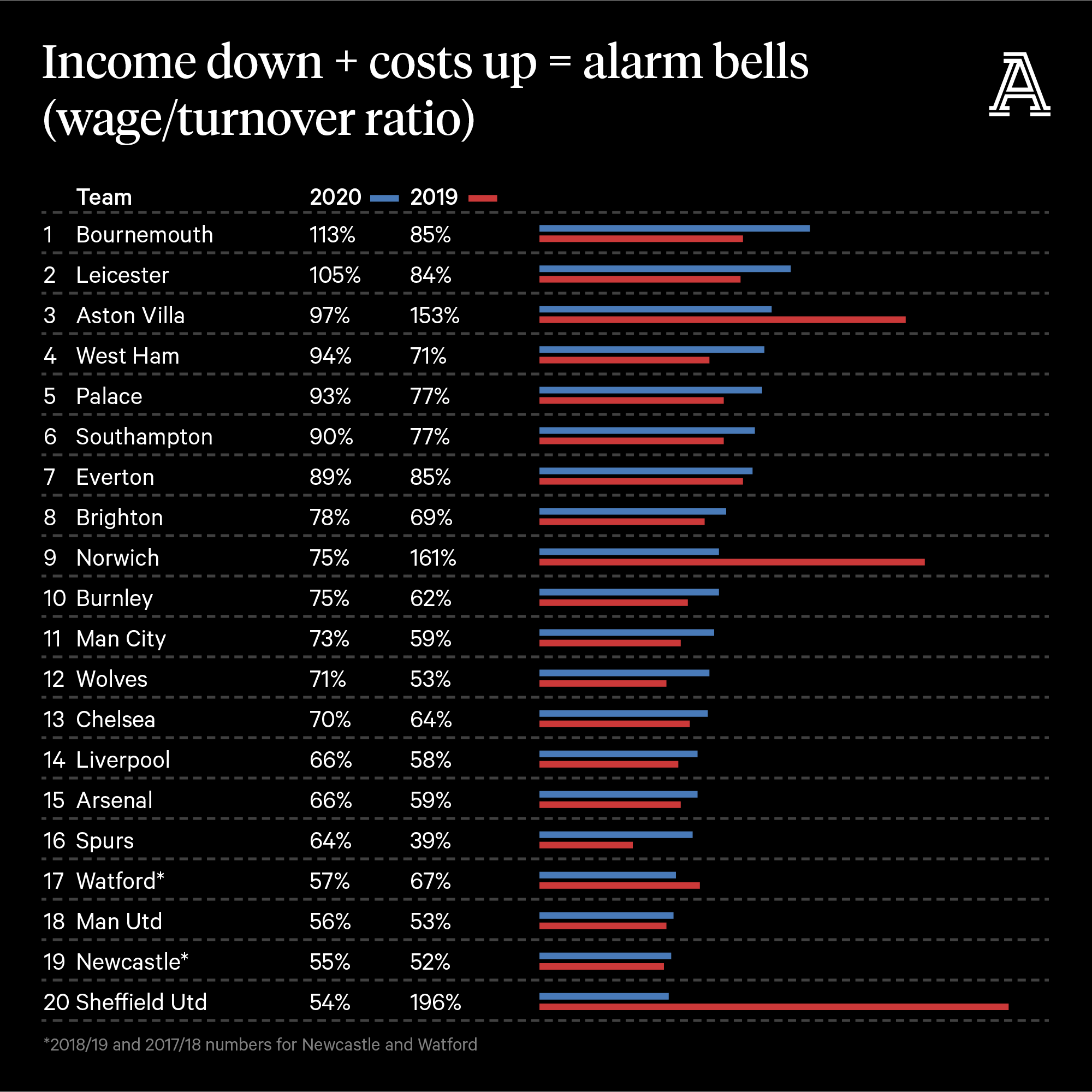

Everton’s attempts to close that chasm where it really matters, on the field, led them to spend 85 per cent of their revenue on salaries in 2019 and 89 per cent of it in 2020. Adding James Rodriguez and others to the squad this season will do nothing to lower that ratio closer to the 70 per cent level that UEFA believes is sustainable.

The club’s combined loss for the last two seasons is £250 million and that is before a brick in their new £500 million stadium has been laid. Not that many believe you can realise an architect’s drawing that posh at a World Heritage Site by a river for half a billion pounds, either.

But that is the price of not settling for one’s station in Premier League life these days. Southampton’s loss for the same period is more than £125 million, West Ham’s is close to £100 million and Brighton and Leicester are about £90 million down.

In many ways, it is these frightening numbers that caused the Big Six to conspire with Real Madrid and the rest to create a Super League and why that plot was so disgraceful.

Famous clubs spending more than 85 pence of every pound they earn on wages — just to close the gap — is anathema to the owners of Arsenal, Liverpool and Manchester United. Players for their sports franchises in North America receive less than half of the overall take. That more equitable split (in their eyes, anyway) plus the certainty of never getting relegated equals lots of happy owners.

The problem with sustainable spending

Burnley, Crystal Palace, Norwich and Sheffield United took the not unreasonable decision to extend their accounting years to July 31.

This means they did not defer any of the Project Restart income to their 2020-21 accounts but they did have to include 13 months’ worth of costs. The net result of this timing shift for Burnley, Norwich and Sheffield United is they avoided making a loss last year.

For Burnley, this was a case of more of the same under the careful stewardship of chairman Mike Garlick and his board of local investors. With a relatively small ground, the hit on Burnley’s match-day income caused by COVID-19 was less significant than elsewhere (it fell by £1.7 million, while Manchester United’s dropped by £21 million) and a good run after the resumption of play took Sean Dyche’s side to 10th in the standings, five places higher than in 2019.

Consequently, their revenue only fell from £138 million to £134 million. Furthermore, Burnley kept a lid on wages and did not spend much on transfers. Add that up and you get a break-even figure. In fact, a tax credit of £500,000 actually took them into the black.

As impressive as that is, the most eye-catching number in their accounts is the amount of cash they had built up, more than £80 million as of July 31. Five months later, Burnley were bought by US investment group ALK Capital and that cash helped pay for some of the shares, with a large loan from the UK branch of American private investment firm MSD Partners providing most of the rest.

MSD’s loans cost about nine per cent a year in interest and ALK is understood to have borrowed at least £60 million initially. That fact, plus the absence of any deferred income and Burnley’s slide down the table, means they face a tougher second leg in the COVID-19 Cup than most.

Burnley are, however, starting from a better place than Palace. The south London club have admitted to making a pre-tax loss of £58 million, by far the worst result for the quartet that stretched their accounting periods.

“It is almost impossible to comment on the financial performance of the club without immediately referencing COVID-19 and the huge impact this has had on everything and everyone associated with the club,” wrote chairman Steve Parish in his strategic report, before adding that playing behind closed doors last summer and the rebate had exacerbated Palace’s loss by £11 million.

The fact that Norwich and Sheffield United made profits despite the pandemic is not that surprising, as most promoted clubs make profits in their first seasons in the Premier League thanks to the huge increase in broadcast income. Just to highlight this point, Norwich’s rose from £10 million in the Championship to £90 million in the Premier League, while Sheffield United’s went from £8 million to £117 million.

Those profits usually turn to losses, however, if the clubs remain in the division. Of the 17 clubs that have posted full financial reports for the season, Sheffield United had the lowest wage bill and Norwich the second-lowest. Their differing fortunes on the pitch — the former finishing eighth and the latter 20th — go a long way to explaining why one made a profit of £19 million and the other of just over £2 million, as each place in the table is worth almost £3 million in prize money.

The odd ones out here are Aston Villa, who managed to lose almost £100 million in their first season back in the big time. But, and this is where the timing caveat comes in, they did not move their year-end from May 31, so deferred about £36 million of Project Restart income. The rest of the difference can be explained by Villa’s mid-table wage bill of £109 million and a significant investment in new players.

The latter shows up in the amortisation column of a club’s accounts as the cost of a new signing is stretched, or amortised, across the length of that player’s contract. In accountancy speak, the players are intangible assets and the cost of buying them must be charged or written off over their useful life. Thanks to Jean-Marc Bosman and European competition law, players can leave for nothing at the end of their contracts and their value on the balance sheet must reflect this, too. So, a £30 million striker on a three-year contract will cost the club £10 million a year in amortisation charges.

To return to the promoted trio, Norwich’s amortisation bill in 2019-20 was just under £9 million and Sheffield United’s was £17 million. Villa’s, on the other hand, was £71 million. In fact, while we have used the wage/turnover ratio as an indicator of sustainability, some analysts prefer to look at wages plus amortisation. This gives Norwich a figure of £98 million, Sheffield United £95 million and Villa £180 million.

Was Villa’s outlay worth it? Well, Norwich were 20th last season and Sheffield United will be 20th this season. Villa are 10th and heading for their best financial performance in years. For most clubs in the Premier League, that is the problem with sustainable spending: you tend to end up in the Championship.

The biggest lesson of all

As mentioned, Liverpool’s post-title buzz was somewhat spoiled by a rather shrill note in their accounts from Andy Williams, a senior auditor at Ernst & Young.

“We draw attention to note 1 to the financial statements, which indicate there is a possibility of an extended delay or curtailment to the 2020-21 season and or commencement of 2021-22 season and the additional financing required in these circumstances is not currently committed,” wrote Williams. “These conditions indicate a material uncertainty exists that may cast significant doubt on the group and company’s ability to continue as a going concern.”

A material uncertainty is auditors’ talk for “don’t blame me if this thing goes bust next year, I did warn you” and, in this case, it is almost certainly a tad over the top. But it is also the only material uncertainty note in a Premier League club’s accounts last season. And Liverpool won.

Does that excuse Fenway Sports Group’s various clumsy attempts to balance the books recently (the £77 match-day ticket, the furloughing, the Project Big Picture plot and the Super League hokey-cokey, in case you have forgotten them all)?

No, it does not. But it explains it.

Maybe now, though, if they re-read Willliams’ hyper-cautious note and reflect on the last two weeks of anger, protests and open letters, they and their would-be revolutionaries can reflect on the biggest lesson we can take from the 2019-20 club accounts: “legacy fans” still matter.

Futsal Focus supports the Donate4Dáithí campaign

To follow the Donate4Dáithí campaign, you can visit their website here: www.donate4daithi.org or on Facebook at: https://www.facebook.com/Donate4Daithi you can also donate money to their campaign at: https://www.justgiving.com/crowdfunding/donate4daithi

To learn more about organ donation or to sign up, you can visit https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/ and to sign up: https://www.organdonation.nhs.uk/register-your-decision/donate/

You can read more articles about domestic futsal by going to the top navigation bar or click here

If you like this article and would like to keep updated on Futsal news, developments, etc then you can now follow Futsal Focus via Google News by following our page which will send you an alert as soon as we publish an article so please click here and follow us on Google.

You can also keep updated on Futsal news, developments, etc then please submit your email below in the Subscribe to Futsal Focus option.

Follow Futsal Focus by clicking on Facebook, Twitter, or Instagram or on the social media buttons on the website.

![Validate my RSS feed [Valid RSS]](https://www.futsalfocus.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/valid-rss-rogers.png)